Stephen Wallis

writer / editor / storyteller

Leonardo and the Salvator Mundi - Town & Country

The $450,000,000 Question

Could the most-anticipated work in the year’s buzziest exhibition be one that isn’t there at all?

By Stephen Wallis

October 21, 2019

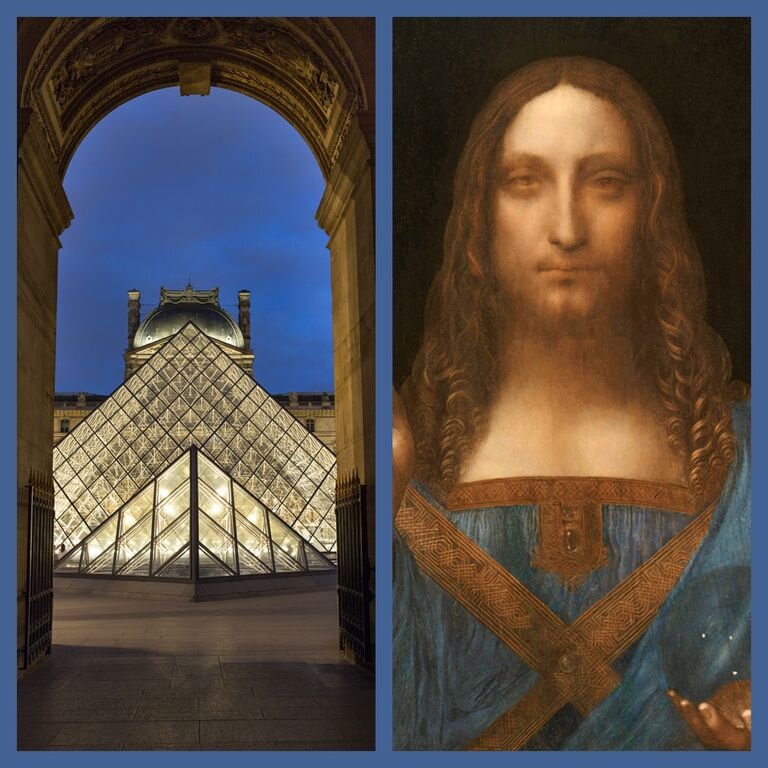

Is it in or is it out? That question has been the talk of the art world (and beyond) in the run-up to the Louvre’s blockbuster fall Leonardo da Vinci exhibition, the headliner among multiple shows organized to mark the 500th anniversary of the Renaissance master’s death.

Opening on October 24, the exhibit features international loans of major works to complement the Louvre’s own trove of 22 Leonardo drawings and five paintings (fewer than 20 of his paintings survive). One of the paintings is the Mona Lisa, which is returning to its usual spot after renovations to its gallery. But the work on everyone’s mind is the Salvator Mundi, a rediscovered depiction of Christ painted around 1500 that became the most expensive artwork ever sold when a member of the Saudi royal family paid $450 million for it at Christie’s two years ago.

Its inclusion in the show seemed to be a foregone conclusion when the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which has a partnership with the French museum, announced that the painting would be part of its inaugural exhibitions last fall. But those plans were indefinitely postponed just weeks before the opening, and now no one seems to know where the work—which has not been seen in public since it left Christie’s—actually is.

With gossips and reporters alike focusing on the status of the Salvator Mundi—one account placed it on the yacht of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman—there is renewed attention to whether the painting should be attributed to Leonardo himself or to his workshop. It has been suggested that doubts about the painting prompted the Saudis to reconsider lending it, or gave the Louvre cold feet about showing it, a claim the museum has denied.

“The public debate has been conducted on an incredibly poor level,” says Martin Kemp, a Leonardo scholar who supported the unequivocal attribution to the artist that was assigned to the Salvator Mundi when it was included in an exhibition at London’s National Gallery in 2011. “It has been triggered by a lot of sensationalism around the record price. It is also triggered by a fair amount of racism—that the Arabs have bought it, and they’ve made a dreadful mistake.”

Adding fuel for doubters are statements by Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Carmen Bambach (who recently published the four-volume Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered) crediting most of the Salvator Mundi to one of the artist’s assistants, and Ben Lewis’s new book, The Last Leonardo, which fans the debate over the painting’s authorship and questions the proposed provenance that connects the dots back to Leonardo. Lewis suggests that the Salvator Mundi might be doomed to a state of attribution limbo but notes that exhibiting it at the Louvre could tip the scales. “Some would still look at it cynically,” he says, “but at that point you’d have to say that this is more or less certified.”

At press time, the odds seemed slim that the painting would make it into the Louvre show, which promises to be Paris’s premier attraction this fall with or without the Salvator Mundi. Of course, it would be a mistake to underestimate a work with such flair for dramatic turns. In the span of 60 years the Salvator Mundi has gone from being a badly damaged, overpainted wreck that sold for less than $60 at a British auction to the $450 million trophy of a Saudi crown prince.

For now the argument over the Salvator Mundi goes on, with respected experts offering divided opinions. “What an incredible split—it’s an incredible, once-in-a-lifetime story,” Lewis says. “The picture itself is such an adventure. What painting has had so many ups and downs?”