Stephen Wallis

writer / editor / storyteller

Modigliani Fakes - Art + Auction

The Modigliani Mess

His canvases sell for millions. He is also one of the most faked artists of the 20th century. Now, competing catalogue raisonné projects threaten to complicate a historically troubled market.

By Stephen Wallis

April 2001

New York—Page 38 of the 1996 book Modigliani: Témoignages, the fourth volume of Christian Parisot’s catalogue raisonné of the works of Amedeo Modigliani, features a painting titled Tête de femme (“Head of a Woman”), dated 1915. Two pages later, a painting of a reclining nude, titled Nu couché and dated 1916, occupies a dramatic double-page spread. Parisot, a 53-year-old art history professor at the University of Orléans who has devoted much of his career to studying Modigliani’s work, is not the first scholar to publish these paintings. They, along with three dozen other works in Témoignages (“testimonies”) also appear in a 1970 Modigliani catalogue raisonné prepared by Joseph Lanthemann.

But Lanthemann’s catalogue is widely acknowledged to contain numerous mistakes, and these two paintings, says Marc Restellini, are most certainly not the work of Modigliani. Restellini, 36, is director of the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris and has for the past four years been preparing his own catalogue raisonné of Modigliani’s paintings and drawings under the aegis of the Wildenstein Institute. He says that lab tests on the Nu couché in Parisot’s book prove that Modigliani could not possibly have been its author: Analysis conducted at University College London revealed the presence of titanium white, a pigment that was not available until after the artist’s death. And Tête de femme, he says, needs no scientific study—it is obviously not by Modigliani.

These are not the only instances in which Parisot and Restellini have reached contrasting conclusions about works attributed to Modigliani. Both men will tell you that they are not rivals, but if you press them a little, they’ll each give reasons why he and not the other should be considered a trusted authority on Modigliani’s work. The volleys—delivered in generally guarded tones—have ratcheted up since January, when Parisot announced that he was organizing a new committee to research, authenticate and publish the “definitive” catalogue raisonné of the artist’s oeuvre. In other words, to do exactly what Restellini has been doing since spring 1997.

Despite Restellini’s statement that he does not want to “get into a war between experts—we want to stay absolutely outside of these things” and despite Parisot’s insistence that the new committee is not being set up in opposition to Restellini, as one well-placed observer aptly (if crassly) puts it, “there’s obviously a major pissing match going on.”

The stakes in this battle are potentially high. Intensely popular, Modigliani’s paintings sell for huge sums—four have broken the $10 million barrier at auction since November 1998. To establish that a painting is or isn’t by Modigliani creates or negates millions of dollars in value. Complicating matters is the fact that Modigliani is among the most faked artists of the entire 20th century, and his legacy has been notoriously plagued by shoddy scholarship—or worse. “Shark-infested waters” is how one dealer describes the Modigliani market. Another calls it “a minefield.”

“Only somebody who would need their head examined would pay a market price for a painting attributed to Modigliani without getting some kind of professional advice,” says Michael Findlay. A longtime 19th- and 20th-century art specialist at Christie’s who is now with Acquavella Galleries in New York. The issue of where to turn for the final word on works by Modigliani that are not already established could be complicated by the introduction of Parisot’s committee, Findlay notes, although he adds that he has not spoken with anyone on the Modigliani committee or discussed its existence with colleagues in the trade or at the auction houses. “If they are presenting themselves as different from or in any sense better than Restellini,” he says, “then I can only say that this is going to muddy the waters. Because that, in effect, will be a glove thrown down as a challenge and will force every dealer, collector and, to some extent, museum curators and auction house people to make a choice as to which catalogue raisonné to accept.”

Findlay’s fear is that people will embrace either the Parisot committee or Restellini based on which one accepts their paintings. “I’m not excited by the prospect that there are possibly going to be two competing experts in a field where, for many years, there has been no living person, only Ceroni.”

Ambrogio Ceroni, who died in 1970, is the only universally accepted Modigliani authority. The catalogues he published in 1958 and 1965 and later updated (in Italian in 1970 and French in 1972) are the starting point for anyone researching a picture attributed to the artist. It is thought that among the 337 paintings that Ceroni included in his final catalogue, he made almost no mistakes. But it is clear that Ceroni was unable to catalogue every single authentic painting, and just how many genuine pictures exist is a matter of significant debate.

According to Parisot, there are at least 50 genuine non-Ceroni paintings that are known. He says that Ceroni indicated there were some 80 pictures he was unable to include in his catalogue because he simply could not locate them. Restellini insists that number is too high. “Modigliani painted five or six paintings a month, so you arrive at a total of around 350 or 360,” he says. “But not 420—that’s impossible.”

—

Over the years, numerous Modigliani catalogues and books have been published with false paintings. Indeed, fakes have been around since shortly after the artist’s death. When Modigliani succumbed to tuberculosis in Paris in January 1920, at age 35, very few records of his output existed. During his lifetime, he achieved minimal recognition, and his work wasn’t worth much. But that began to change shortly after he died, and it is widely held that his last dealer, Léopold Zborowski, was involved in commissioning fakes or completing canvases left unfinished in the artist’s studio and selling them. A Polish immigrant who became Modigliani’s official representative in 1918—after dealer Paul Guillaume canceled his contract with the troubled artist—Zborowski is said to have been perpetually short of money.

“The value of Modigliani got up so high just after he died, and Zborowski was the only source for works,” says Restellini. “He got requests and started to make Modiglianis. So we have very old paintings that are completely fake.”

Modigliani is perhaps tempting to forgers because the distinctive style of his figures—the elongated faces and necks; the curved or angular noses; the small, pursed mouths; the sloping shoulders; the almond eyes—might seem, superficially at least, easier to fake than other artists’ work. According to Restellini, for every authentic Modigliani painting there are three fakes, and for every drawing, nine fakes.

David Norman, director of Impressionist and modern art at Sotheby’s New York, says he has not encountered as many fakes as Restellini describes, but agrees that among 20th-century artists Modigliani is “one of the handful that is most often faked.” He adds that he sees plenty of works that he would “not necessarily count as fakes but perhaps wishful thinking on the part of owners.”

Given the proliferation of Modigliani forgeries, it’s hardly surprising that a significant number of them have entered the market and been published as genuine. “I have occasionally gone through old sale catalogues from the ’30s and ’40s and have looked at works that, to my eye, most anybody today would reject,” says Norman. “The Modigliani field always seems to have been rife with contending scholars and sources, and Ceroni remains the only book that everybody universally accepts. In every other book you can easily find a work that somebody calls into question.”

That includes Parisot’s, which dealers and auction house specialists contacted by Art & Auction allege contain a number of questionable works and obvious fakes. Parisot, who has held a chair at the University of Orléans since 1978, says his “lifetime passion” for Modigliani began when he met the artist’s daughter, Jeanne Modigliani, in 1975. The two worked together until her death in 1984, and Parisot has since organized numerous exhibitions and published (by his count) more than 20 books on Modigliani and the School of Paris, including his unfinished Modigliani catalogue raisonné.

Parisot says that Jeanne Modigliani entrusted him with an unspecified amount of archival material related to her father’s work. He claims that she also assigned him the droit morale, a group of legal rights in France belonging to artists that are designed to give them the authority to protect the integrity of their work. Some of these rights pass to the artist’s heirs, the most significant of which is the right to perform authentications. But droit morale or not, Parisot’s authority as a Modigliani specialist has not been universally acknowleged.

Meanwhile, with the backing of the Wildensteins—the respected publishers of more than 40 artists’ catalogues raisonnés and owners of the Wildenstein & Company gallery in New York—Restellini quickly became the primary authenticator of works attributed to Modigliani. Howard Rutkowski, head of Impressionist and modern art at Phillips, de Pury & Luxembourg, who previously worked at Sotheby’s, recalls, “Until Restellini starting vetting pictures, essentially we wouldn’t take a picture if it was not in Ceroni.” But today, as dealers will tell you, if you want to sell a Modigliani that is not in Ceroni, you’ll probably need Restellini’s blessing.

When Restellini began working on his catalogue raisonné, however, he was not exactly a household name in the field of Modigliani scholarship. A lecturer in art history at the Sorbonne from 1988 to ’93, he had prepared a small exhibition of Modigliani’s portraits and landscapes in ’88 in Paris (for which he borrowed a group of drawings from Parisot) and a retrospective of the artist’s work in ’92 in Tokyo. But Restellini says that his experience with the artist’s work dates back to his childhood. “My grandfather was very close with the main sponsor of Modigliani,” he explains. “I first held a Modigliani in my hands when I was five years old.”

That sponsor was Jonas Netter, “a partner of Zborowski,” who, Restellini explains, “between 1918 and 1920, paid Modigliani FF500 a month.” Netter also bought a number of Modigliani’s paintings and kept lists, bills of sale and correspondence related to his purchases. Thanks to the family connection, Restellini has access to these documents. He claims that he is the only scholar who has access to this archival material, as well as to material provided to him by a relative of Roger Dutilleul, another important collector of Modigliani’s work.

The fact that Restellini has these archives may well have played a role in the Wildenstein Institute’s decision to work with him. He says the project came together a couple of years after he was introduced to Daniel Wildenstein (who oversees the institute) by Joachim Pissarro, who is currently preparing a catalogue raisonné at the institute on the works of his great-grandfather, Camille Pissarro.

Not everyone is pleased with the authority that Restellini now wields, and his working methods have occasionally caused frustration among those awaiting decisions on works sent to him for examination. One auction house specialist raises concerns about Restellini’s reliance on scientific analysis. “We had a painting, and he was concerned that one element of it was not by the artist,” the specialist recalls. “Stylistically, I was looking at it with all my colleagues and saying, Of course it is. And we were held up for months having to send the picture so that a little speck could be taken and analyzed. That kind of stuff can make you crazy, because we knew it was right and he determined that it was right but we missed a sale.”

Restellini defends his use of scientific analysis as essential to understanding how Modigliani worked from year to year—what types of paint he used, whether he made underdrawings, etc. Such information, he says, is needed in order to compare works and make judgments about authenticity. “It’s the only way to do serious research on Modigliani,” he says. “We have objective, scientific analysis, which confirms what the eye sees. I refuse to be pushed by pressure from the market, and that’s a problem because an auction house will come here with a painting and they want to know in two or three days whether or not we will include the painting [in the catalogue raisonné]. But sometimes we must compare, we must understand, we must make different analyses.”

Several members of the trade note that, however slow Restellini might be, they respect his thoroughness and insistence on inspecting every work firsthand. Restellini spends only two afternoons a week at the Wildenstein Institute, and he receives no compensation for his work, except for the royalties he will earn on the catalogue raisonné, whose publication is tentatively planned for late 2002 or 2003.

—

Unveiled at a sparsely attended press conference at the Carlyle Hotel in New York on January 23 and detailed in an information packet that was sent out to journalists, auction houses and some 250 international galleries, the new committee assembled by Parisot is being trumpeted as a “blue-ribbon panel” of “foremost scholars” whose purpose is “to safeguard, research and authenticate [the] work of Amedeo Modigliani.” In a mission statement included in the press materials, Parisot noted that “the controversy over the artist’s oeuvre has escalated” and that “the controversy must be resolved.”

The committee’s members, who are unpaid and are to meet two to four times a year, are (in addition to Parisot): Jean Kisling, the son of artist Moïse Kisling—a close friend of Modigliani’s—and author of the catalogue raisonné of his father’s work; Masaaki Iseki, director of the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum and a specialist in 20th-century Italian art; Claude Mollard, an art historian and delegate of the French Ministry of Culture; and Marie-Claire Mansecal, archivist of the works of Georges Dorignac, a secondary School of Paris artist who was related by marriageto Modigliani’s last mistress, Jeanne Hébuterne. André Schoeller, a Paris expert in late 19th- and 20th-century art, resigned from the committee shortly after it was unveiled, citing health reasons.

Officially headquartered in New York, the committee also has offices in Paris and Livorno, Italy (Modigliani’s birthplace). Funding for its activities is provided by Canale Arte Publishing in Turin, Italy, which will publish the group’s catalogue raisonné. All decisions on whether to accept or reject works for the catalogue will be made by majority vote, and each member has one vote. The committee’s first working meeting is scheduled for this month in Paris. Among the issues to be addressed at the meeting—according to a handwritten agenda faxed to Art & Auction—is the legal basis on which Parisot and the committee claim the sole right (assigned, Parisot asserts, by Jeanne Modigliani) to call their catalogue the official “catalogue raisonné.”

But the committee faces an uphill battle in gaining acceptance from the art market. A number of dealers and auction house specialists express skepticism about the credentials of the individual committee members to serve as authenticators of Modigliani’s work.

Indeed, veteran Paris dealer Daniel Malingue doesn’t mince words in voicing his doubts: “This committee is a complete joke. Jean Kisling is a good friend of mine, but I don’t think that he or the other people know enough to be members of the committee. Parisot went fishing and got people who all the world can see don’t know enough about Modigliani to say whether something is good.” Malingue believes that the committee will have minimal impact because, he says, “nobody will take their catalogue seriously.”

Respected Geneva-based art adviser Marc Blondeau, is equally forthright in his dismissal of the committee. “It’s a nonsense for me—it’s a non-event,” he says. “How can we trust someone who made a catalogue that includes some very dubious and obvious fake paintings? Parisot can’t be trusted.” Blondeau adds that “the only person with an eye in that group is André Schoeller, and he has resigned.” (Schoeller organized the 1987 sale of the Georges Renand collection in Paris, featuring the 1917 Modigliani nude La Belle Romaine, which became the most expensive work by the artist ever sold at auction when it brought $16.8 million at Sotheby’s New York in November 1999.) When contacted by Art & Auction, Schoeller’s son, Eric (who is an expert in modern and contemporary art), confirmed that his father had stepped down for health reasons, and added, “We are on good terms with Mr. Parisot and with other members of the committee.”

Most auction house specialists, meanwhile, offer cautiously neutral reactions to the committee, indicating that they are taking a wait-and-see attitude. One specialist concedes that he doesn’t “know of anyone who sees this committee as having a shot at being credible” but explains that he is hesitant to publicly dismiss the group. “They could make a fuss and claim that something is fake when it’s not,” he says. “A purchaser at an auction might see this and might not understand the nuances, and we might get stuck having to cancel a sale, or the work could get devalued. I don’t fear these people’s judgment, but they could still cause problems down the line, which is why I think people at the auction houses are going to refrain from saying that they won’t use them.”

—

As part of efforts to promote the committee, Parisot is eager to draw distinctions between his group and the Wildenstein Institute. Speaking with Art & Auction (through an interpreter) at the committee’s New York offices in January, he suggested that there was no certainty that Restellini’s catalogue would ever be published. To lend weight to this possibility, he claimed that to his knowledge only one of numerous catalogues raisonnés started by the Wildenstein Institute has been published—the works of Claude Monet. In fact, some 40 have been published.

Parisot also emphasized that there are no collectors or dealers on the committee. “We do not have paintings worth millions like Wildenstein, so we can be more independent,” he says. “Wildenstein has financial weight, we have intellectual weight.”

In a rare interview with Art & Auction conducted at the institute in early February, Daniel Wildenstein insisted that the gallery has no involvement with the institute’s catalogues. He said that he does not own a single work by Modigliani nor has he bought or sold any of the dozen or so previously uncatalogued works discovered by Restellini.

His reasons for supporting Restellini have nothing to do with financial interests. “I knew Ceroni very well, and he was a real connoisseur of Modigliani,” he said. “Later on, some other books were published on Modigliani that seem to me to be very wrong—they accepted pictures that should not have been accepted. If I had bought all the Modiglianis that were discovered since Ceroni, we would be ruined.”

In the January interview, Parisot made a point of noting that the Wildenstein Institute has twice been taken to court in France by owners of works that Restellini has not accepted for his catalogue. One case involves a drawing of a young girl that appeared in an October 1997 sale at the Bern, Switzerland, auction house Dobiaschofsky. The undated drawing had been consigned along with a drawing of a young boy, and each work was given an estimate of SF290,000 ($199,000). Both failed to sell, and a few months later the owner took them to Restellini for examination. In letter dated March 5, 1998, Restellini wrote to the owner informing him that he did not intend to include either drawing in his catalogue. He believes that the two drawings are by the same hand but that “there are elements that are not credible” as works by Modigliani. In August 1999, the owner sued the Wildenstein Institute over the drawing of the girl, and the Tribunal de Grande Instance in Paris ordered a new evaluation of the work by the expert Guy-Patrice Dauberville, who determined that it is, in fact, genuine. The owner had purchased the portrait of the girl for FF1.7 million ($252,000) in a March 1991 sale conducted by Paris auctioneer Pierre Cornette de Saint-Cyr, and the portrait of the boy for SF230,000 ($177,000) in December 1990 from Bevaix, Switzerland, auctioneer Pierre-Yves Gabus. Both drawings are included in the second volume of Parisot’s catalogue raisonné, published in 1991. The parties are currently awaiting a ruling from the court.

The other case involves a drawing of a woman in a hat that was last sold in June 1985 by Paris auctioneers Ader, Picard and Tajan in June 1985 for FF379,000 ($55,000). Again, when the drawing was submitted to Restellini, he indicated that he did not intend to include it in his catalogue. The owner took the matter to court, and another expert, Marie-Hélène Frinfeder, is currently evaluating the work. For now, Restellini stands firmly by his opinion. As support he points to a copy of an exhibition catalogue from a 1968 show in Japan that features handwritten notations by Ceroni. Beneath the illustration for this particular drawing, Ceroni clearly wrote “non,” which Restellini interprets to mean that Ceroni did not believe the drawing is right.

Ceroni included in his catalogues fewer than 180 of Modigliani’s drawings, which are much more problematic to authenticate than his paintings. (Modigliani also made stone sculptures, 25 of which survive and are well known.) “The drawings are very difficult,” says Malingue. “Nobody knows. If people were prepared to put their own heads on the line saying, ‘I’m sure this is good and this is fake,’ all the heads would be cut off. Everybody will make mistakes in the authentication of [Modigliani’s] drawings.”

—

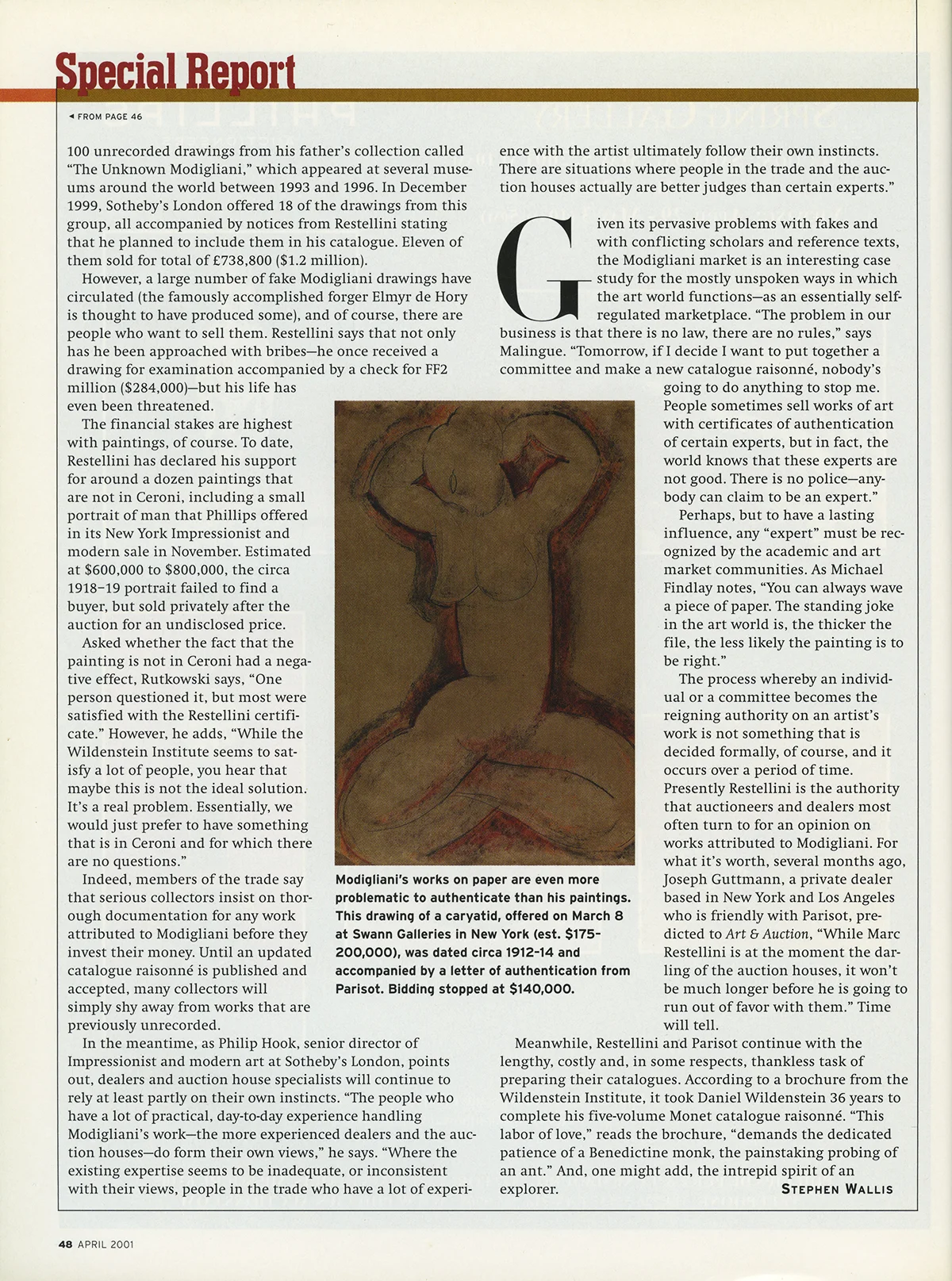

On March 8, Swann Galleries in New York offered a colored drawing of a caryatid figure attributed to Modigliani, dated circa 1912–14, with an estimate of $175,000 to $200,000. Twice offered at auction in the early ’90s, the work was accompanied by a 1994 letter of authentication from Parisot, but it is not in Ceroni and had not been seen firsthand by Restellini. Swann had sent photographs to Restellini’s office, but did not respond to his request to submit the drawing to him for direct examination because there wasn’t enough time, says Swann prints and drawings specialist Todd Weyman. Despite the fact that Swann featured the work in its ads and promotional material for the sale, bidding on the caryatid stopped at $140,000. However, according to Weyman, none of the clients interested in the drawing expressed concern about its authenticity.

Because Modigliani’s drawings are less well documented than his paintings, previously unknown examples are more likely to surface. Nearly a decade ago Noël Alexandre—the son of the earliest significant collector of Modigliani’s work, Paul Alexandre—organized an exhibition of more than 100 unrecorded drawings from his father’s collection called “The Unknown Modigliani,” which appeared at several museums around the world between 1993 and 1996. In December 1999, Sotheby’s London offered 18 drawings from this group, all accompaniedby notices from Restellini stating that he planned to include them in his catalogue. Eleven of them sold for total of £738,800 ($1.2 million).

However, a large number of fake Modigliani drawings have circulated (the famously accomplished forger Elmyr de Hory is thought to have produced some), and of course, there are people who want to sell them. Restellini says that not only has he been approached with bribes—he once received a drawing for examination accompanied by a check for FF2 million ($284,000)—his life has even been threatened.

The financial stakes are highest with paintings, of course. To date, Restellini has declared his support for around a dozen paintings that are not in Ceroni, including a small portrait of man that Phillips offered in its New York Impressionist and modern sale in November. Estimated at $600,000 to $800,000, the circa 1918–19 portrait failed to find a buyer but sold privately after the auction for an undisclosed price.

Asked whether the fact that the painting is not in Ceroni had a negative effect, Rutkowski says, “One person questioned it, but most were satisfied with the Restellini certificate.” However, he adds, “While the Wildenstein Institute seems to satisfy a lot of people, you hear that maybe this is not the ideal solution, and it’s a real problem. Essentially, we would just prefer to have something that is in Ceroni and for which there are no questions.”

Indeed, members of the trade say that serious collectors insist on thorough documentation for any work attributed to Modigliani before they invest their money. Until an updated catalogue raisonné is published and accepted, many collectors will simply shy away from works that are previously unrecorded.

In the meantime, as Philip Hook, senior director of Impressionist and modern art at Sotheby’s London, points out, dealers and auction house specialists will continue to rely, at least in part, on their own instincts. “The people who have a lot of practical, day-to-day experience handling Modigliani’s work—the more experienced dealers and the auction houses—do form their own views,” he says. “Where the existing expertise seems to be inadequate or inconsistent with the views of people in the trade who have a lot of experience with the artist, ultimately, people in the trade follow their own instincts. There are situations where people in the trade and the auction houses actually are better judges than certain experts.”

—

Given its pervasive problems with fakes and with conflicting scholars and reference texts, the Modigliani market is an interesting case study for the mostly unspoken ways in which the art world functions—as an essentially self-regulated marketplace. “The problem in our business is that there is no law, there are no rules,” says Malingue. “Tomorrow, if I decide I want to put together a committee and make a new catalogue raisonné, nobody’s going to do anything to stop me. People sometimes sell works of art with certificates of authentication of certain experts but, in fact, the world knows that these experts are not good. But there is no police. Anybody can claim to be an expert.”

Perhaps, but to have a lasting influence, any “expert” must be recognized by the academic and art market communities. As Michael Findlay notes, “You can always wave a piece of paper. The standing joke in the art world is, the thicker the file, the less likely the painting is to be right.”

The process whereby an individual or a committee becomes the reigning authority on an artist’s work is not something that is decided formally, of course, and it occurs over a period of time. Presently Restellini is the authority that auctioneers and dealers most often turn to for an opinion on works attributed to Modigliani. For what it’s worth, several months ago, Joseph Guttmann, a private dealer based in New York and Los Angeles who is friendly with Parisot, predicted to Art & Auction, “While Marc Restellini is at the moment the darling of the auction houses, it won’t be much longer before he is going to run out of favor with them.” Time will tell.

Meanwhile, Restellini and Parisot continue with the lengthy, costly and, in some respects, thankless task of preparing their catalogues. According to a brochure from the Wildenstein Institute, it took Daniel Wildenstein 36 years to complete his five-volume Monet catalogue raisonné. “This labor of love,” reads the brochure, “demands the dedicated patience of a Benedictine monk, the painstaking probing of an ant.” And, one might add, the intrepid spirit of an explorer.

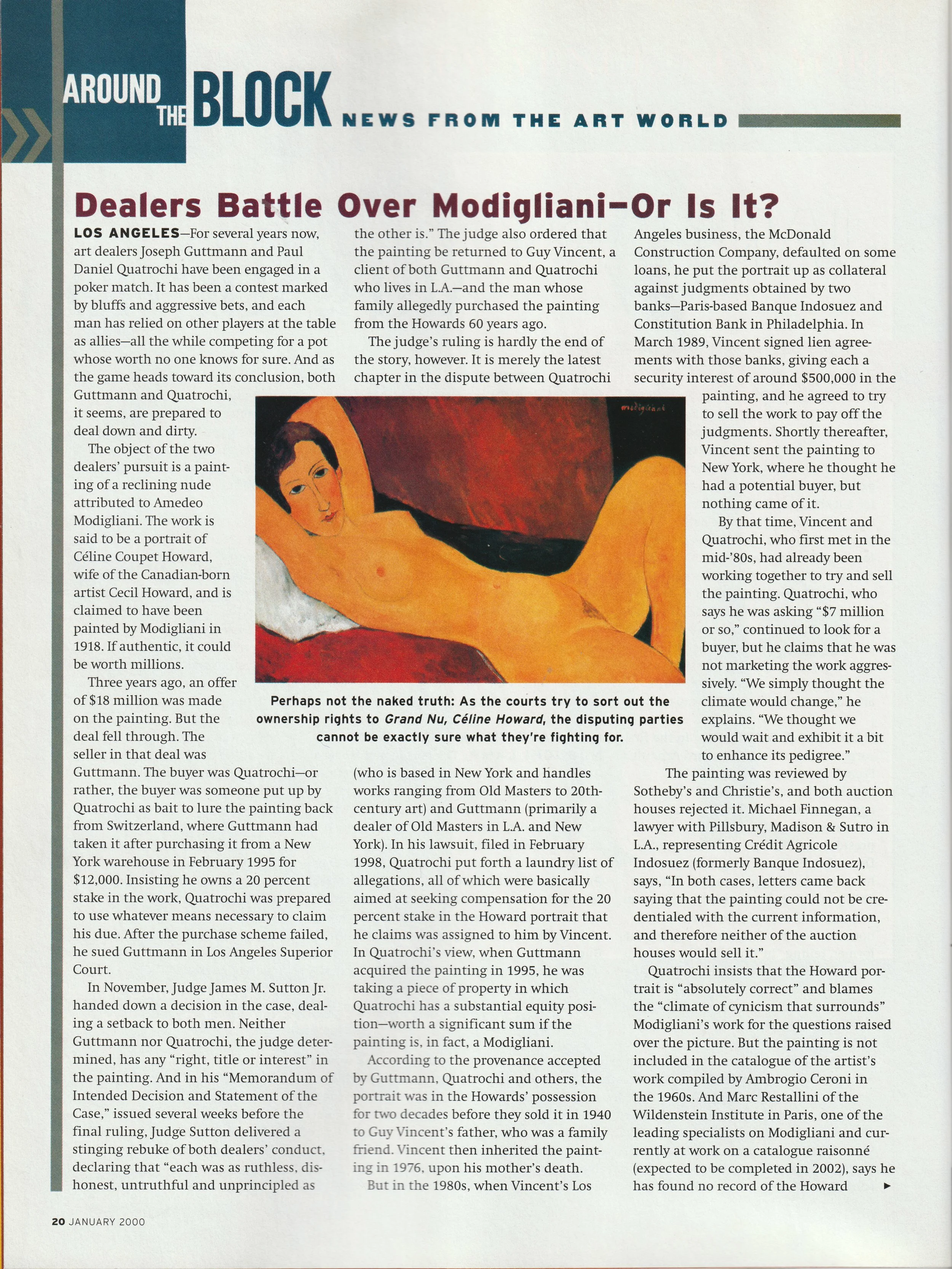

Dealers Battle Over Modigliani—Or Is It?

By Stephen Wallis

January 2000