Stephen Wallis

writer / editor / storyteller

Mono-Ha - Art In America

Mono-ha Moment

magazine Dec 5, 2011

http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazine/mono-ha-moment/

In the thoroughly mined field of midcentury art, few stones have been left unturned by ferreting curators or opportunistic dealers and collectors. So it’s somewhat surprising that, in the American art world at least, the mention of Mono-ha still brings mostly shrugs. But thanks to interest among some high-profile players, there’s growing curatorial and market awareness of the short-lived Japanese art movement, which lasted roughly from 1968 to 1973.

Mono-ha, usually translated as “School of Things,” was the name given to a loosely associated group of artists, most of whom graduated from Tokyo’s Tama Art University during the youth-driven unrest of the late ’60s. Their work was stridently anti-modernist-primarily sculptures and installations that incorporated basic materials such as rocks, sand, wood, cotton, glass and metal, often in simple arrangements with minimal artistic intervention. More experiential than visual, Mono-ha works tended to demand patience and reflection. Many were also ephemeral. For both artistic and practical reasons, the often site-specific pieces were usually destroyed. There were no buyers, and the artists couldn’t or wouldn’t preserve them. In other words, Mono-ha was deeply at odds with what today’s market craves most: brand-name, high-gloss art with instant visual pop.

And yet, four decades later, a market for Mono-ha is emerging, though its supply is inherently limited. Leading the way is Korea-born Lee Ufan, the group’s best-known figure, who, despite a long, successful career in Europe and Asia, remained largely unrecognized in the U.S. until just a few years ago [see A.i.A., Dec. ’08]. Following an installation of his work at the Palazzo Palumbo Fossati during the 2007 Venice Biennale, his status has skyrocketed in this country, thanks to his first American solo shows at Pace Gallery in New York (2008) and Blum & Poe in Los Angeles (2010), and especially his eye-opening retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum this past summer.

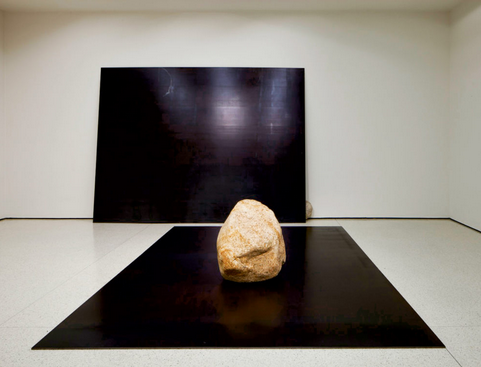

Auction prices for Lee’s “From Line” and “From Point” paintings of the ’70s and early ’80s have topped $1 million (his record is $1.9 million, set at Sotheby’s in May 2007). Re-creations of his early “Relatum” stone-and-steel sculptures now sell mostly in the $300,000 to $500,000 range, though the largest pieces can approach $1 million, according to Blum & Poe partner Tim Blum. “The Guggenheim show helped a lot,” said Pace Gallery owner Arne Glimcher. “Many works were sold during the exhibition.” Glimcher noted that Lee’s early works were made at a time when critical and market focus in the U.S. was on American artists. “Now it’s a very pluralistic, international art world,” he said.

Nonetheless, most of the dozen or so other Mono-ha artists have stayed completely under the American market’s radar, not to mention out of the critical discourse and art history books. That should change somewhat this winter, with a landmark show organized by Blum & Poe that will feature major works by Mono-ha’s key figures. Running Feb. 25 to Apr. 14, it’s the biggest show the gallery has ever mounted and will occupy its entire Culver City building. There will also be a substantial catalogue, edited by the show’s organizer, Mika Yoshitake, an independent curator and Mono-ha specialist.

“Anything that relates to Mono-ha that was iconic is going to be included,” said Blum, who lived and worked in Japan for almost five years in the ’90s, speaks the language and represents Lee as well as Takashi Murakami and a few other Japanese artists. “Like everybody else, I’ve seen a lot of this work only in poor black-and-white reproductions-with the exception of a few small gallery shows in Japan.”

In addition to a handful of important works by Lee (none of which were in the Guggenheim exhibition), highlights of the Blum show include an outdoor installation of Koshimizu Susumu’s August 1970/2011-Cutting a Stone, a piece that involves creating a single split in a large rock. There are four installations by Suga Kishio, including his 1970 Infinite Situation II (steps), in which sand is packed onto a flight of stairs so that just the edges of the steps are visible, both concealing and drawing attention to their structure. And Sekine Nobuo’s Phase-Mother Earth (1968), the work that is sometimes credited with giving birth to Mono-ha, will be re-created off-site, at a location yet to be announced. Originally made for a sculpture exhibition in Kobe’s Suma Rikyuo Park, it consists of an 8½-foot-tall cylinder of earth standing next to an identically sized hole in the ground-a powerful iteration of pure form and material that deteriorates over time.

Blum declined to cite prices for individual works, in part because some have already been sold. He says pricing has been challenging, as “there’s no market and we’re starting slightly from scratch.” But he noted that “major works from this period can be had for under half a million dollars.”

The Dallas Museum of Art is one of the museums, along with the Guggenheim, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and London’s Tate Modern, that has an active interest in Mono-ha. Already, the DMA has acquired several works in collaboration with local collectors Howard Rachofsky and Deedie Rose, and other significant acquisitions are expected to be announced soon.

Lee Ufan: Relatum, 1978/2011, two steel plates, 110 ¼ by 82 ½ by 3 ½ inches each, and two stones, each approx. 27 ½ inches high, in “Marking Infinity” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo David Heald. Courtesy National Museum of Art, Osaka.

In the thoroughly mined field of midcentury art, few stones have been left unturned by ferreting curators or opportunistic dealers and collectors. So it’s somewhat surprising that, in the American art world at least, the mention of Mono-ha still brings mostly shrugs. But thanks to interest among some high-profile players, there’s growing curatorial and market awareness of the short-lived Japanese art movement, which lasted roughly from 1968 to 1973.

Mono-ha, usually translated as “School of Things,” was the name given to a loosely associated group of artists, most of whom graduated from Tokyo’s Tama Art University during the youth-driven unrest of the late ’60s. Their work was stridently anti-modernist-primarily sculptures and installations that incorporated basic materials such as rocks, sand, wood, cotton, glass and metal, often in simple arrangements with minimal artistic intervention. More experiential than visual, Mono-ha works tended to demand patience and reflection. Many were also ephemeral. For both artistic and practical reasons, the often site-specific pieces were usually destroyed. There were no buyers, and the artists couldn’t or wouldn’t preserve them. In other words, Mono-ha was deeply at odds with what today’s market craves most: brand-name, high-gloss art with instant visual pop.

And yet, four decades later, a market for Mono-ha is emerging, though its supply is inherently limited. Leading the way is Korea-born Lee Ufan, the group’s best-known figure, who, despite a long, successful career in Europe and Asia, remained largely unrecognized in the U.S. until just a few years ago [see A.i.A., Dec. ’08]. Following an installation of his work at the Palazzo Palumbo Fossati during the 2007 Venice Biennale, his status has skyrocketed in this country, thanks to his first American solo shows at Pace Gallery in New York (2008) and Blum & Poe in Los Angeles (2010), and especially his eye-opening retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum this past summer.

Auction prices for Lee’s “From Line” and “From Point” paintings of the ’70s and early ’80s have topped $1 million (his record is $1.9 million, set at Sotheby’s in May 2007). Re-creations of his early “Relatum” stone-and-steel sculptures now sell mostly in the $300,000 to $500,000 range, though the largest pieces can approach $1 million, according to Blum & Poe partner Tim Blum. “The Guggenheim show helped a lot,” said Pace Gallery owner Arne Glimcher. “Many works were sold during the exhibition.” Glimcher noted that Lee’s early works were made at a time when critical and market focus in the U.S. was on American artists. “Now it’s a very pluralistic, international art world,” he said.

Nonetheless, most of the dozen or so other Mono-ha artists have stayed completely under the American market’s radar, not to mention out of the critical discourse and art history books. That should change somewhat this winter, with a landmark show organized by Blum & Poe that will feature major works by Mono-ha’s key figures. Running Feb. 25 to Apr. 14, it’s the biggest show the gallery has ever mounted and will occupy its entire Culver City building. There will also be a substantial catalogue, edited by the show’s organizer, Mika Yoshitake, an independent curator and Mono-ha specialist.

“Anything that relates to Mono-ha that was iconic is going to be included,” said Blum, who lived and worked in Japan for almost five years in the ’90s, speaks the language and represents Lee as well as Takashi Murakami and a few other Japanese artists. “Like everybody else, I’ve seen a lot of this work only in poor black-and-white reproductions-with the exception of a few small gallery shows in Japan.”

In addition to a handful of important works by Lee (none of which were in the Guggenheim exhibition), highlights of the Blum show include an outdoor installation of Koshimizu Susumu’s August 1970/2011-Cutting a Stone, a piece that involves creating a single split in a large rock. There are four installations by Suga Kishio, including his 1970 Infinite Situation II (steps), in which sand is packed onto a flight of stairs so that just the edges of the steps are visible, both concealing and drawing attention to their structure. And Sekine Nobuo’s Phase-Mother Earth (1968), the work that is sometimes credited with giving birth to Mono-ha, will be re-created off-site, at a location yet to be announced. Originally made for a sculpture exhibition in Kobe’s Suma Rikyuo Park, it consists of an 8½-foot-tall cylinder of earth standing next to an identically sized hole in the ground-a powerful iteration of pure form and material that deteriorates over time.

Blum declined to cite prices for individual works, in part because some have already been sold. He says pricing has been challenging, as “there’s no market and we’re starting slightly from scratch.” But he noted that “major works from this period can be had for under half a million dollars.”

The Dallas Museum of Art is one of the museums, along with the Guggenheim, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and London’s Tate Modern, that has an active interest in Mono-ha. Already, the DMA has acquired several works in collaboration with local collectors Howard Rachofsky and Deedie Rose, and other significant acquisitions are expected to be announced soon.

Jeffrey Grove, the museum’s senior curator of contemporary art, said, “We’re looking for singular Mono-ha objects that fold in with other pieces in the collection-postwar abstraction, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, Arte Povera-to give a more international perspective to the story of art from that period.” This past summer Grove featured a couple of recent Mono-ha acquisitions in his “Silence and Time” exhibition, including a series of Nomura Hitoshi photographs from 1970 in which the artist meticulously documented the evaporation of blocks of dry ice as a study in ephemerality and the dematerialization of the art object.

The Nomura works were purchased from New York gallery McCaffrey Fine Art, which is the other primary source in the U.S. for Mono-ha material. Like Blum, Fergus McCaffrey lived in Japan and speaks the language, and he’s done shows of work by Nomura, Lee, Enokura Koji and Takamatsu Jiro, who was a teacher at Tama Art University when the key Mono-ha artists were students there. McCaffrey calls Takamatsu the “most important Japanese artist in the ’60s because of his influence.” McCaffrey organized the first solo show of the late artist’s work in the U.S. two years ago, and when he took a group of Takamatsu’s photographs of photographs from 1972-73 to the Independent art fair in New York last March, he said, “they were vacuumed up by major museums” at around $50,000 to $60,000 each.

From Jan. 6 to Mar. 17, McCaffrey will be showing pieces by Haraguchi Noriyuki, an artist who is connected to Mono-ha, though, as McCaffrey noted, “he is very political in a way Mono-ha is not.” The artist is also creating a full-size replica of the tail of an American Corsair A7 fighter jet, based on a print he made in 1972, when there were protests against the U.S. military bases in Japan. Prices, McCaffrey said, will range from $50,000 to $650,000.

Interestingly, there’s hardly any market for Mono-ha in Japan itself. One exception is the Kamakura Gallery in Kanagawa, which was originally located in Tokyo and has been showing Mono-ha artists for many years. Most recently, the gallery presented re-creations of early sculptures that Sekine made for a 1970 exhibition in Milan using rock and either stainless steel or fluorescent bulbs. The gallery declined to give prices but according to sources familiar with the work, they are in the same range as comparable pieces at Blum & Poe.

Allan Schwartzman, a private dealer and curator who works with Rachofsky, Rose and the Dallas Museum of Art as well as Brazilian collector Bernardo Paz, said of his discovery of Mono-ha a few years ago, “It’s rare to come upon something in our field that you really didn’t know anything about. From a collecting perspective, the work is comparatively undervalued.”

The necessary re-creation of pieces raises questions when trying to establish value. Yoshitake, the curator of the Blum show, noted that while “it was very natural for the artists to install their works and then discard them,” such practices are “not compatible with the values of preservation and originality that are so important to museums and collectors.” For the first time, ownership agreements and certificates of authenticity are being drawn up with the artists or their estates. Yoshitake points to the work of Sol LeWitt and Félix González-Torres as precedents.

The key, Glimcher said, is that everything is being done according to the artists’ wishes and specifications. “If Lee Ufan’s works were being posthumously re-created, I wouldn’t have any use for them, but he’s doing it himself,” he said. “It would be a tragedy for those works to exist only in photographs.”